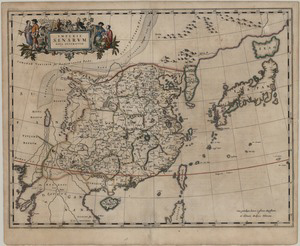

This map of China comes from the first Western atlas of China, Atlas Sinensis (Chinese Atlas) by Martino Martini (1614-1661). The Atlas Sinensis (https://lbezone.hkust.edu.hk/bib/b528225) was published by Johannes Blaeu (1596-1673), first in 1655 as in independent regional Atlas, then as part two of volume 10 (dedicated to Asia) of his 1662 Great Atlas. Martini’s map is completely different from the preceding western ones, in being based to a great extent on Chinese textual and cartographic sources, as well as on scientific observations by the Jesuit missionaries themselves.

Martino Martini was an Italian Jesuit missionary to China, which he reached in 1643 travelling from Lisbon to Macao. After having learnt the language and collected geographical information, Martini was sent back to Rome on an official mission, taking with him both Chinese maps and books as well as his own maps and notes. The Dutch East India Company detained him in Batavia (nowadays Jakarta) and asked him to produce an updated map of China for them. Martini did it, and took the occasion to sail to Amsterdam first, and to publish there both his Atlas and other historical treatises on China. That ensured that his maps had wide circulation, unlike others by his Jesuit predecessors and colleagues such as Aleni (1582-1649) and Michael Boym (1612-1659), which laid unpublished in the Vatican archives.

Martini’s map was based strongly on the work of the Ming cartographer Luo Hongxian (1504-64) and most likely relied on input from Blaeu, official cartographer of the Dutch East India Company, for the detailed costal coverage. For the first in Western maps, Korea is represented as a peninsula and Japan, to which the Atlas dedicates also a separate map in appendix (https://lbezone.hkust.edu.hk/bib/b537628), is portrayed in a much more satisfactory way than in any previous attempt The Gobi desert (called Lop in the map) uses for the first time in Western cartography dots as convention for deserts (a convention common in Chinese maps).

The illustration in the cartouche at the top right corner shows pairs in (supposedly) Chinese customs as well as local fruits and crops. The map has no text on the back, but in the Atlas Sinensis it is followed by a long Latin preface and by 15 maps of Chinese Provinces. The 20 pages long preface discusses the name of China, definitely clarifying the different nomenclature used for the country, from the Classical Serica and Sina to Marco Polo’s Cathay and Mangi and to the contemporary China, covering in encyclopedic fashion the country’s main crops, population, history and culture, to end with a table of coordinates for the major cities.

Chinese Customs

Chinese Customs

Martini’s map supplanted Ortelius’ as the standard for around 80 years, until the appearance of maps by another Jesuit, the French d’Anville (1697-1782).

Sources- CITCO 2003 June

- Nebenzahl, Kenneth, Mapping the Silk Road and beyond: 2,000 years of exploring the East, London: Phaidon, 2004, 136-137.

- Klemp, Egon and Wightman, Alison, Asien auf Karten : von der Antike bis zur Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts = Asia in maps: from ancient times to the mid-19th century,Weinheim: VCH Verl., 1989, map 61.

- Boleslaw Szcześniak “The Seventeenth Century Maps of China. An Inquiry into the Compilations of European Cartographers”, Imago Mundi, Vol. 13 (1956), pp. 116-136

- Caterino, Aldo (ed), Riflessi d'Oriente : l'immagine della Cina nella cartografia europea. Trento : Il Portolano ; Centro studi Martino Martini], 2008, 109-110.

- De Peuter, Stanislas (2011). Martino Martini’s Jesuit cartography of the Middle Kingdom: some historio-carto reflections on then, in-between and now (part I). BIMCC Newsletter 39 : 16-24; (part II). BIMCC Newsletter 40 : 11-17, (part III) BIMCC Newsletter 41: 8-12.

- http://www.bimcc.org/uploads/newsletters/nl39.pdf

- http://www.bimcc.org/uploads/newsletters/nl40.pdf

- http://www.bimcc.org/uploads/newsletters/nl41.pdf